In December 2016, the Information Law and Policy Centre co-organised an event celebrating the 250th anniversary of the world’s first law providing a right to information. It was hosted by free expression NGO, Article 19 at the Free Word Centre and supported by the Embassies of Sweden and Finland. A full programme of the event and the audio files are available on the Campaign for Freedom of Information website. In this post, Judith Townend and Daniel Bennett reflect on a few of the key themes discussed at the event.

Accessing information may no longer feel like a pressing problem. We live in an age of global telecommunications, the internet and the smartphone with access to ubiquitous 24/7 media coverage on demand. Our data is collected, tracked, mapped and analysed by social media networks, search engines, commercial enterprises, governments and public authorities around the world. And yet, 250 years after the first law providing for a right to information was passed, the right for us – the public – to access information relating to the administration of state power remains a struggle.

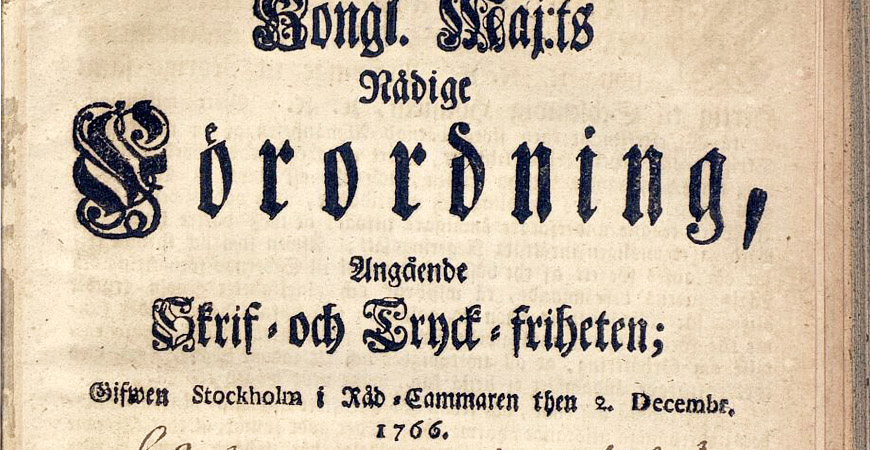

Our ‘Freedom of Information at 250’ event sought to put this struggle into its historical context. The event celebrated and commemorated the signing into law of ‘His Majesty’s Gracious Ordinance Relating to Freedom of Writing and of the Press’ on 2nd December 1766.¹ Enacted by the Riksdag (parliament) of Sweden – which then also included Finland – this was the world’s first law to promise public access to governmental information.

The underlying rationale for the law was perhaps best articulated by Peter Forsskal. In his 1759 pamphlet, Thoughts on Civil Liberty, he wrote:

“…it is also an important right in a free society to be freely allowed to contribute to society’s well-being. However, if that is to occur, it must be possible for society’s state of affairs to become known to everyone, and it must be possible for everyone to speak his mind freely about it. Where this is lacking, liberty is not worth its name.”

The 1766 law pioneered public access to state information helping sow early seeds for similar rights to public information which have developed in the centuries since. Over 100 countries now have right to information laws.

Across two moderated discussions in the afternoon and an evening panel, the FOI at 250 event on 8th December 2016 commemorated, celebrated and scrutinised the adoption of this law. Participants also discussed its relevance and significance today, in both national and global contexts.

One of the central themes to emerge from the event was the way in which the passing of Freedom of Information legislation across the world and its successful implementation could only develop within a culture of openness and transparency.

One of the central themes to emerge from the event was the way in which the passing of Freedom of Information legislation across the world and its successful implementation could only develop within a culture of openness and transparency.

Discussing the 1766 law, historian Jonas Nordin noted that the law’s significance rests in its documentation of a pioneering shift away from a culture of secrecy towards one in which openness became the norm. Today, he noted that Swedish civil servants have inculcated a culture of openness – a necessary condition for the effective functioning of Sweden’s current system of transparency. Similarly, when discussing the piloting of the Freedom of Information Act through the Scottish Parliament, Lord James Wallace of Tankerness argued that culture change as well as legislation was required to bring the legislation to the UK.

The UK’s own Freedom of Information (FOI) Act 2000 was famously described by former Prime Minister Tony Blair as one of the biggest regrets of his time in government, but it has survived politicians’ scepticism as well as bureaucratic and legal obstruction. The Act not only obliges UK public authorities to publish certain material about their activities, but also allows people to request information from them.

In November 2016, the legal basis for the FOI Act was reinforced by a landmark European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) ruling. In the case of Magyar Helsinki Bizottság v. Hungary, the Grand Chamber ruled that public watchdogs have a right to information in the public interest from public authorities under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Speaking at the event, Maurice Frankel, Director of the Campaign for Freedom of Information (CFOI) believed that this ECtHR ruling opened the way for legal challenges to provisions in the FOI Act for ‘absolute exemptions’ – circumstances when public authorities do not have to disclose information. Looking forward, Frankel also wanted to see the imposition of tighter time limits in which authorities need to respond to FOI requests and the extension of the FOI Act to include government contractors.

The latter point was addressed in the evening panel session by the UK Information Commissioner, Elizabeth Denham, who stated that the public had a right to know about public services regardless of whether the provider was a public, private or third sector organisation. The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) is submitting a report to Parliament on transparency and outsourcing in 2017.

In order to develop Freedom of Information further, Denham stated that she would also be pressing for a statutory duty for public authorities to fully document their decisions. She believed this would provide a solution to the vast quantities of ‘ephemeral data’ created by the use of text messages, emails and instant messaging in government. If government is not to grind to a halt in the deluge of data that should be made available to the public, however, Denham argued that a shift towards ‘access by design’ is required.

Considered in light of the first Swedish/Finnish law of 1766, Denham’s comments reinforced how the challenge of freedom of information has both changed and remained the same. In 250 years, a revolution in information technology has transformed culture from one of information scarcity to information overload bringing with it challenging new problems even as it drives forward possibilities for more ‘open’ government. But at the same time, those who continue to argue that freedom of information is essential for a healthy democracy today are inspired by many of the same principles as those who first conceived the 1766 law. The future of freedom of information and the struggle for the public’s ‘right to know’ will continue to contain echoes from this past.

¹ A new English translation of the 1766 law is available here.

Dr Judith Townend is a lecturer in media and information law at the University of Sussex and former Director of the Information Law and Policy Centre.

Photos: The Embassy of Sweden