This post was originally written by Sonia Livingstone, Professor of Social Psychology in the Department of Media and Communications and Gianfranco Polizzi, PhD researcher at LSE, for the LSE Media Policy Project Blog.

We live in a society increasingly based on the collection and processing of personal information by public institutions (e.g., through biometrics and CCTV cameras) and by corporations like Google and Facebook. This poses a range of challenges. The Cambridge Analytica scandal highlights the risk of corporate data misuse. In addition, “criminals are using child data to create” fake identities, which “can go undiscovered for years”. Also of concern, children are constantly targeted with personalised ads which can be “manipulative” and “deceptive” or age-inappropriate and potentially harmful. The long term consequences for biased or discriminatory decisions affecting children’s future life chances are unknown.

Key research findings

Based on focus group discussions, the Children’s Data and Privacy Online project explored what 11-16-year-old children in the UK know about their data and privacy, finding that:

• Children care about their privacy. But they best understand it in interpersonal terms, not in the context of how their data is used by internet corporations or public institutions.

• When they realise how businesses monetise (and can misuse) their data, they feel outraged and powerless, since the alternative to giving consent is to be socially excluded.

• They want 1) online platforms to have child-friendly terms and conditions, 2) their accounts to be private by default, 3) to be able to delete content permanently, 4) for their data not to be shared beyond the app or service they chose to use.

• Parents are concerned about what happens with their children’s data but know little about it.

• Teachers trust their schools with safeguarding.

What should be done?

To ensure that children enjoy their rights in and through the digital environment, we need to re-imagine it by including the voice of children. Given what they know and want to change about their data and privacy, multiple actors should take action:

Tech companies

Internet corporations and social media like Facebook should re-design their platforms in ways that 1) value children and respect their rights, 2) minimise online risks, 3) are more transparent, so that users know what happens to their data, 4) avoid legalese in their terms and conditions and make reporting and readdress more child-friendly. To some extent, all major platforms engage in self-regulation, curbing copyright infringements and demoting suspicious content. But they have not done enough to protect children, not least because their use of nudge techniques to keep users glued to their devices is at the heart of their business models. So is their lack of transparency, which capitalises on users’ lack of privacy.

Government and public bodies

As we cannot expect platforms to fully embrace ethical principles that clash with their business models, there should be some intervention from governments and public bodies. The UK’s Internet Commissioner’s Office (ICO) is developing an age-appropriate design code of practice for online services to boost data protection for children as a requirement of the UK’s Data Protection Act 2018.

Schools and teachers

Schools should set a good example of how to handle children’s data and parental consent needs to be better addressed. Parents often do not know whether their children have “been signed up to systems using their personal data”. And many are not informed that their data is stored and shared with others. As for the school curriculum, educators teach internet safety as part of Computing and Personal, Social, Health and Economic (PSHE) education, focusing, for example, on cyberbullying and pornography. But for students to learn about privacy beyond the interpersonal context, more should be done to teach digital literacy with emphasis on the broader digital environment, how internet corporations operate and handle users’ data, and with what implications for society.

Parents

They have a responsibility to provide children with advice and insights into how their data is used. But they need answers in the first place. Civil society organisations (e.g., Parent Zone, Internet Matters), media outlets such as the BBC, and academics have made available resources designed to help parents navigate parenting in the digital age. The Children’s Data and Privacy Online project’s privacy toolkit is an example, based on the research findings. Parents themselves need to be pro-active in seeking support. And since many share online a considerable amount of information about their children, they should consider potential negative consequences for their children’s privacy.

Civil society, the media industry and academics

These actors play a key role in raising awareness among, and providing resources to, children, parents and teachers about online data and privacy. Civil society has also a responsibility to represent the public and make policymaking accountable. Charities like 5Rights, for instance, campaign for children’s digital rights and support ICO’s age-appropriate design code. Academics, furthermore, have a responsibility to gather evidence through their research and inform the public and policymakers.

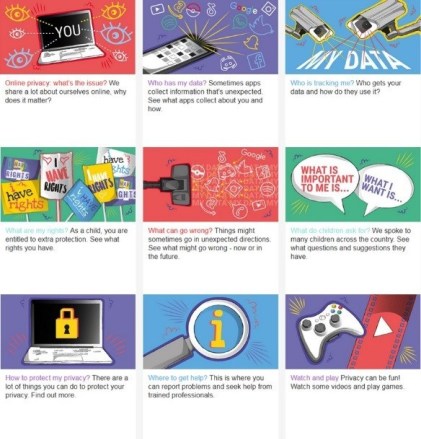

An online privacy toolkit

To promote children’s understanding of the digital environment and support them to make good decisions about privacy online, the team behind the Children’s Data and Privacy Online project developed an online privacy toolkit. Developed with the participation of children and freely available at www.myprivacy.uk, the toolkit is aimed at children of secondary school age, with resources also for parents and educators.