In this guest post Atalanta Goulandris, former barrister and PhD researcher at City University London, reflects on the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies’ contribution to the Being Human festival: the ‘Humanity of Lawyers’, which focused on the work of the Bar…

In this guest post Atalanta Goulandris, former barrister and PhD researcher at City University London, reflects on the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies’ contribution to the Being Human festival: the ‘Humanity of Lawyers’, which focused on the work of the Bar…

There is a general lack of knowledge about the Bar, with misconceived notions of what barristers do, how they work and their professional interaction with the solicitor branch and the public. The ‘humanity’ of barristers is not something people generally think or talk about. This was, however, the starting point for the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies’ (IALS) contribution to the national Being Human festival in November 2015, which is led by the School of Advanced Study, University of London, in partnership with the Arts & Humanities Research Council and the British Academy.

Whilst promoting the event – a follow up to last year’s ‘Humanity of Judging’ at the Supreme Court – it was striking how many chuckled (or guffawed) at the notion that barristers have humanity! Common portrayals of barristers, whether in the press or emanating from the Ministry of Justice, are of ‘fat cat lawyers’ or clever, slippery-tongued advocates, who are cool and detached. Aside from being simplistic and one dimensional, these characterisations ignore the complexity of barristers’ professional role, the ethics that underpin their thoughts and actions and the difficult real life situations in which they perform as professionals and as people.

Our venue was the Inner Temple, one of the four Inns of Court in London, places most members of the public would not usually visit – and therefore appropriate to this year’s festival theme, ‘Hidden and Revealed’. Although much of barristers’ work takes place in public courtrooms, much also remains hidden from view, with many working in the cloistered surroundings of the Inns of Court or in chambers across the provinces.

At our event on 19th November – deliberately pitched at a wide public audience – many remarked that they had never been inside the Temple, had no idea it was there and were astonished by the beauty of the buildings, the gardens and the interior of the magnificent Parliament chamber. If nothing else, the physical surroundings in which barristers work were revealed.

Our five speakers, from academia and practice, approached the topic from different perspectives.

Our five speakers, from academia and practice, approached the topic from different perspectives.

Dr Justine Rogers, joining us via a pre-recorded video from the University of New South Wales in Sydney, talked about her three months shadowing pupil (trainee) barristers as part of her PhD research, which took an anthropological approach in considering their professional identity formation.

Dividing her time between commercial/chancery, criminal and family law chambers, she was struck by the intensity and the humanity of their professional lives. Citing examples, she charted the taxing emotional challenges pupils and barristers face on a daily basis, whether it was being humiliated by a judge for getting something wrong, being shouted and spat at by an upset and unhappy client in the cells underneath a criminal court or having to deploy strategic sympathy (sometimes real!) to a distressed client in order to provide support.

Dividing her time between commercial/chancery, criminal and family law chambers, she was struck by the intensity and the humanity of their professional lives. Citing examples, she charted the taxing emotional challenges pupils and barristers face on a daily basis, whether it was being humiliated by a judge for getting something wrong, being shouted and spat at by an upset and unhappy client in the cells underneath a criminal court or having to deploy strategic sympathy (sometimes real!) to a distressed client in order to provide support.

She witnessed pupils develop the ability to detach themselves from some of these challenges in order to be able to perform their role professionally and manage their fears to appear supremely confident, when very often they were not, having just started out in their careers. Of barristers more generally, she remarked that although they were aware that they were often disliked, they felt it was more important to get things right for the client than be popular. Justine found that the barristers she observed were generous with their time, witty and good company and although they downplayed their ethical role as fearless, independent and honest advocates, these aspects of their professional life were a source of great pride.

Professor Andy Boon, of City University London spoke next and mindful of the lay audience, gave a brief historical overview of lawyers and the rule of law. Explaining the role lawyers played in developing the framework of rights under the rule of law, he then cited three aspects of a lawyer’s role: neutrality, partisanship and non-accountability. Focusing on two barristers at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, he illustrated how essential it was for them to not be morally judgmental about their clients, how they had to give every client their best shot and how they could not be accountable of the moral consequences of their representation, however controversial that might be.

Professor Andy Boon, of City University London spoke next and mindful of the lay audience, gave a brief historical overview of lawyers and the rule of law. Explaining the role lawyers played in developing the framework of rights under the rule of law, he then cited three aspects of a lawyer’s role: neutrality, partisanship and non-accountability. Focusing on two barristers at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, he illustrated how essential it was for them to not be morally judgmental about their clients, how they had to give every client their best shot and how they could not be accountable of the moral consequences of their representation, however controversial that might be.

Thomas Erskine (1750-1823) was accused of being ‘shameful’ by the Attorney General, for defending Thomas Paine in his trial for seditious libel. His response was both courageous and very human:

‘I will forever, at all hazards, assert the dignity, independence and integrity of the English bar, without which impartial justice, the most valuable part of the English constitution, can have no existence. From the moment that any advocate can be permitted to say that he will or will not stand between the Crown and the subject arraigned in the court where he daily sits to practice, from that moment the liberties of England are at an end.’ In Rt Hon. Lord Widgery, ‘The Compleat Advocate’ (1975) 43:6 Fordham Law Review

Andy’s second example was Henry Brougham (1778-1868) who defended Queen Caroline in 1820 in a trial brought by her husband, King George IV. Even faced with the likelihood of undermining the credibility of the monarch, he felt it was his duty to defend her, however dangerous that might be for him personally.

‘(a)n advocate, in the discharge of his duty, knows but one person in all the world, and that person is his client. To save that client by all means, and expedients, and at all hazards and costs to other persons, and among them, to himself, is his first and only duty; and in performing his duty, he must not regard the alarm, the torments, the destruction he may bring upon others. Separating the duty of a patriot from that of an advocate, he must go on reckless of consequences, though it should be his unhappy fate to involve his country in confusion.’ In Nightingale (ed) Trial of Queen Caroline (1821)

Both examples serve to illustrate the importance of the rule of law, and the courage, integrity and humanity of the advocates that defended it in the past and continue to do so in the face of continuous challenges.

The audience then heard from the first of two barristers, Robin Howard, of 1 Gray’s Inn Square chambers. ‘Are we human? I hope we are. Do we not bleed?’ he opened, before describing the context in which most barristers work, namely of representing clients in extremis. Whether it concerned their liberty, livelihood, home, family, possessions or health, more often than not by the time clients meet their barrister they are in trouble and the stakes are high. For him it is a privilege to be called upon in these circumstances to use his strength, effort and skills in acting for them.

The audience then heard from the first of two barristers, Robin Howard, of 1 Gray’s Inn Square chambers. ‘Are we human? I hope we are. Do we not bleed?’ he opened, before describing the context in which most barristers work, namely of representing clients in extremis. Whether it concerned their liberty, livelihood, home, family, possessions or health, more often than not by the time clients meet their barrister they are in trouble and the stakes are high. For him it is a privilege to be called upon in these circumstances to use his strength, effort and skills in acting for them.

He agreed with Justine Rogers that some form of detachment or ‘carapace’ was necessary in order for him to carry out his work professionally. He also brought up the question that all barristers, whatever their practice, get asked: how can you defend someone you know is guilty? Robin’s answer was you never know the client is guilty, unless he/she tells you and that the barrister’s opinion of innocence or guilt is irrelevant, every client having the right to a fair hearing. For him the real pressure comes when defending someone he believes to be innocent and if he has failed to secure their acquittal, it is those cases that he remembers years later and feels bad about.

Mavis Maclean, University of Oxford, spoke next about her ten years of research, observing barristers, solicitors and judges in the family courts. One study involved shadowing family law barristers. Having worked for the Lord Chancellor’s Department and its successor, the Ministry of Justice, Mavis was taken aback by the negative view most of the civil servants and politicians held about lawyers generally and with regard to family lawyers how they perceived them to be profiting from tax payers money (via legal aid, when it was available for private family law cases) by stirring things up between divorcing couples.

Mavis Maclean, University of Oxford, spoke next about her ten years of research, observing barristers, solicitors and judges in the family courts. One study involved shadowing family law barristers. Having worked for the Lord Chancellor’s Department and its successor, the Ministry of Justice, Mavis was taken aback by the negative view most of the civil servants and politicians held about lawyers generally and with regard to family lawyers how they perceived them to be profiting from tax payers money (via legal aid, when it was available for private family law cases) by stirring things up between divorcing couples.

Her research did not support this view – rather, she found that all the legal professionals did everything they could to diffuse the tense situations in family law cases, focusing more on negotiation and sorting out housing and child issues in an attempt to avoid contested court hearings. She was impressed by the delicacy, tact, respect and grace with which barristers, often quite young, handled difficult cases and distressed clients.

She observed them spending many unpaid hours after a case was over, talking with clients and helping them find the courage and self-respect to carry on, when, for example, they had lost custody of their children. Her assessment of barristers could not have been further from the unpleasant, tough image portrayed by politicians, whom she mused were perhaps more concerned with their own career advancement when proposing clever and money saving reforms at the expense of the work family lawyers did.

Public law and human rights barrister Caolifhionn Gallagher was the last speaker. She agreed that the public perception of barristers was mainly negative, with ‘money grabbing’ and ‘dishonest’ images prevailing, placing lawyers on a par with estate agents, bailiffs, politicians, used car salesman and traffic wardens, amongst others, as the most hated professions. She suggested that perhaps this was because many people only come into contact with lawyers at ‘the worst time of their lives’ and resent needing them or that many don’t really understand what lawyers do or appreciate the amount of hours of work that is involved for what might seem a fairly short hearing. She felt, nonetheless, that many had had positive personal experiences with their own particular lawyer, despite the ‘pale, stale, male’ stereotype so evident in images of barristers.

Public law and human rights barrister Caolifhionn Gallagher was the last speaker. She agreed that the public perception of barristers was mainly negative, with ‘money grabbing’ and ‘dishonest’ images prevailing, placing lawyers on a par with estate agents, bailiffs, politicians, used car salesman and traffic wardens, amongst others, as the most hated professions. She suggested that perhaps this was because many people only come into contact with lawyers at ‘the worst time of their lives’ and resent needing them or that many don’t really understand what lawyers do or appreciate the amount of hours of work that is involved for what might seem a fairly short hearing. She felt, nonetheless, that many had had positive personal experiences with their own particular lawyer, despite the ‘pale, stale, male’ stereotype so evident in images of barristers.

Caolifhionn likened barristers to professional problem solvers, who acted as a conduit in explaining a client’s situation to the court. She remarked that having a young family of her own often drove her to work even harder for those that had lost a family member, her appreciation of their loss being even greater. Much of her work was out of the public eye, but was often the most rewarding. She described calling a duty judge on the phone late at night to seek remedies when a public body had failed in its duty to, for example, find shelter for a child who was homeless or reverse the unlawful separation of a mother and child.

Caolifhionn likened barristers to professional problem solvers, who acted as a conduit in explaining a client’s situation to the court. She remarked that having a young family of her own often drove her to work even harder for those that had lost a family member, her appreciation of their loss being even greater. Much of her work was out of the public eye, but was often the most rewarding. She described calling a duty judge on the phone late at night to seek remedies when a public body had failed in its duty to, for example, find shelter for a child who was homeless or reverse the unlawful separation of a mother and child.

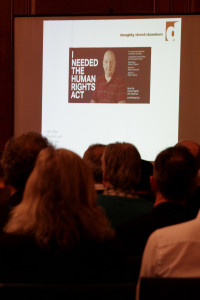

She did not mind being ‘humiliated’ by a judge, as Justine Rogers described, as long as she had done her job properly and highlighted that the only thing that mattered to her was the clients and acting in their best interests. Although Caolifhionn agreed that some form of emotional detachment was necessary to do her job as well as she could, she also felt that this should not prevent barristers from identifying with causes and getting involved in wider campaigning. In her case she was involved in the Act for the Act campaign to promote accurate real life stories of people who have benefited from the Human Rights Act, a meaningful and valuable antidote to the many misconceptions surrounding it.

A lively Q&A discussion followed, before more conversation over

A lively Q&A discussion followed, before more conversation over  drinks.

drinks.

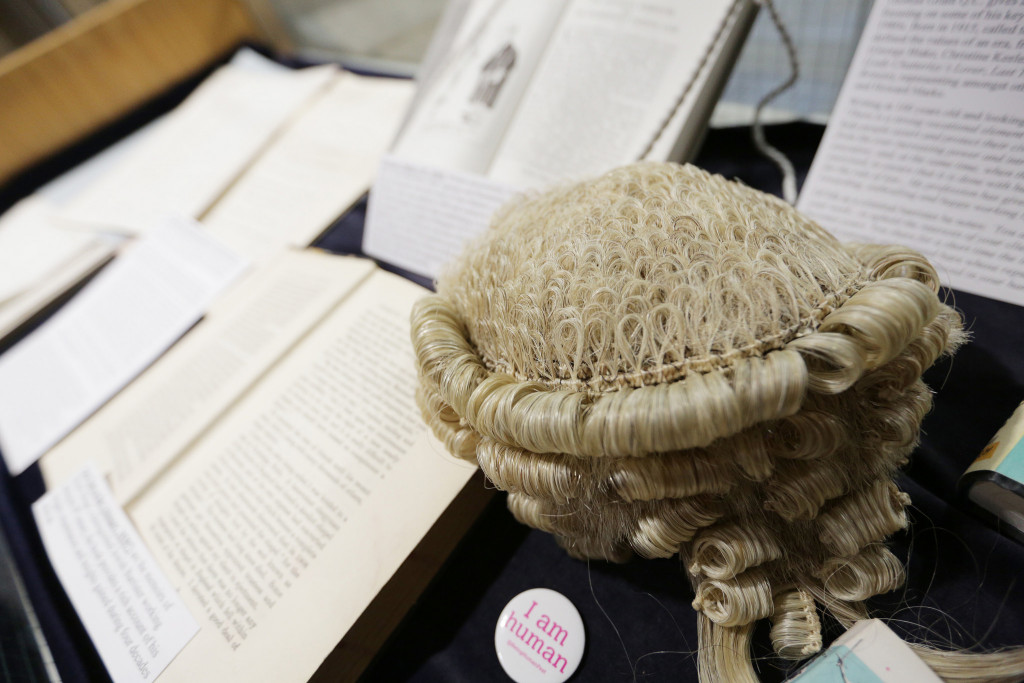

Those who were unable to make this event or would like to know more about the theme might like to pass by the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies at 17 Russell Square where in the foyer there are two cabinet displays on our Humanity of Lawyers theme.

The display includes archival material from the Inner Temple Library, a selection of books written by practitioners and academics, with extensive captions, as well as a display of watercolours by artists Isobel Williams, who has painted court scenes from the Supreme Court and photographs, by Stephane Gripari, of the strike action in 2014, when thousands of barristers, together with other legal professionals refused to work, for the first time in their long history, because of the extensive legal aid cuts imposed on many areas of practice.

This small exhibition will be on display during the spring term.

This small exhibition will be on display during the spring term.

Atalanta Goulandris chaired the Humanity of Lawyers event on 19 November 2015.

A note from organiser Judith Townend at the IALS: we owe a big thanks to numerous people for this event!

- to the School of Advanced Study for funding this event through the Public Engagement Innovators’ fund

- our student volunteers from the University of Sussex law school; photographer Lloyd Sturdy; Nimal Waragoda Vitharana and Muhibul Islam from the IALS for AV and library research support respectively

- our hosts, the Inner Temple – in particular Alice Pearson, Magna Carta Project Manager, for facilitating the event, and Patrick Maddams, sub-treasurer of the Inner Temple, for welcoming us to the Temple on the evening

- all the speakers and our chair and adviser Atalanta Goulandris, who provided us with invaluable guidance in putting together the programme and display.

Thank you all!